10 Questions for Meg Toth

Sometimes I think of my life as a big container with others stacked inside it, like one of those wooden Russian dolls they sell at Christmas.

Chris—the smallest—inside

Niagara Falls, inside

Mateo, inside

my film notebook, inside

my job at FALLOUT, the outer shell

If only I could get down to the innermost container—the essential, most vulnerable one—I’d be OK. I might not even need to go all the way down, just dig through and find the ones contaminating the others. Toss them right into a hazmat dumpster, and then I’d be whole again.

—from Meg Toth’s FALLOUT, Volume 66 Issue 2 (Summer 2025)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

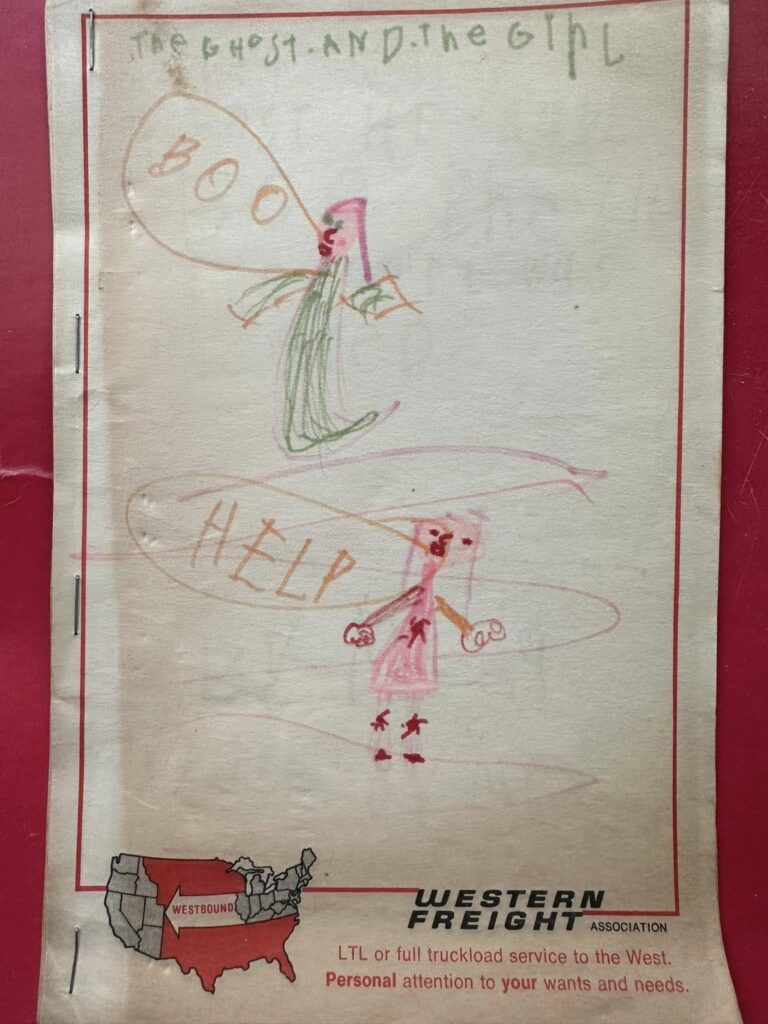

I recently came across a box of childhood belongings at my mom’s house in Cleveland and discovered the first “book” I wrote. It’s written in crayon on Western Freight Association paper, the binding held together with staples. The story is about a girl whose home is haunted by a ghost. (It’s aptly titled “The Ghost and the Girl.” I was a literal child when it came to naming; my family had a gray cat named Gray and an orange cat named Orange.) Eventually, the ghost in the story possesses various family members, and the narrative ends without much resolution. The story is pretty dark and violent—particularly so since I probably wrote it when I was about five. Strangely, though, that story predicts a lot of my current interests in both genre (horror, Gothic, speculative) and themes like family, trauma, and the unknown.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

George Saunders, for sure. FALLOUT is strictly realist, but most of my writing is speculative. I love Saunders’ short fiction, especially how his speculative plots often feel more real than reality. (“Semplica Girl Diaries” is my absolute favorite, and I taught it for years in college literature courses.) Saunders embraces both sentiment and tricky ethical questions, and it’s the bravery of that combination that really speaks to me. My first novel, which I’m currently querying, is about a technology that can bring film characters into the real world, and, influenced by Saunders, it explores the ethical dilemmas that come along with it. It’s also, I hope, funny, which is also a Saunders trademark.

More generally, I’m drawn to artists who experiment with genre in order explore social and political issues. I like film and literature that somehow both conforms to and explodes generic patterns. Some favorites in this vein include Margaret Atwood, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, David Lynch, Carmen Maria Machado, Jordan Peele… I could go on. I’m trying to do something similar in the book I’m currently writing, a Gothic academic novel.

What other professions have you worked in?

I was a college professor for over 15 years before leaving academia for good. But I had many jobs before that. Right after college, I was a social worker at a domestic violence shelter for two years; I worked nights there, alone, from the time I was 22 to 24 years old, which in retrospect is hard to believe. And as a working class kid growing up in a Cleveland suburb, I had a staggering number of jobs, from babysitter and ice cream scooper to McDonald’s cashier and hair salon receptionist (the salon was called Scissor Wizards, and it was run by the “bad” women in my hometown). I mention all this because work is a common theme in my writing, not just FALLOUT. I’m interested in how our jobs shape us, trap us, save us—and the weirder the job, the better.

What did you want to be when you were young?

Well, I wanted to be a writer. And then I spent three decades ignoring that desire—the thing that truly brings me joy—before I finally came to my senses.

What inspired you to write this piece?

I watched Free Solo and got to thinking about the people who have to deal with the messes that thrill-seekers—or adventurers or daredevils or whatever you want to call them—potentially make. That is, there was something about the selfishness of the subject of the documentary that rubbed me the wrong way. You want to pull this stunt? Fine, but if it goes wrong, you aren’t the only one who suffers—there’s someone who literally has to clean up afterwards. I now see how weird it was that this is what I was hyper-focused on, when the documentary is interested in the loved ones of the climber and how they might feel if something went wrong. But what can I say? That’s what stuck with me most, and I thought about it in the back of my mind for years before finally sitting down and starting the story.

I initially thought that’s what the story would be about: a company whose sole purpose is cleaning up messes, with a focus on one of its employees. You wouldn’t believe the amount of research I put into finding out more about this profession—it’s fascinating! But almost immediately, I realized that the story was about what led the protagonist to the job in the first place.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

My hometown, Cleveland, which gets such a bad rap in the national imagination (the river caught on fire!) but is actually an incredible city. It seems like even when I set a piece elsewhere, Cleveland finds a way of creeping in. FALLOUT is no exception.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

My mom, Lynn, and my partner, Mark. They are very different readers. Mark never gives suggestions about content—he reads for typos and sentence-level issues. By contrast, my mom has lots of opinions about content, and she is almost always right. (Not joking—my mom, who reads more voraciously than anyone I know, could have been a professional editor.)

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

Film—100%, no question. Teaching courses on the history and analysis of film for so many years not surprisingly makes you wonder if you could do it yourself. I actually took a production course at NYU a few years back, thinking I’d enjoy film editing, and I swiftly learned that I actually hate it. But I still fantasize about being a cinematographer (the camerawork was my favorite part of the course). And I would love to write a screenplay! I think it would come naturally to me—a lot of my writing is cinematic, and there are parts of my first novel that are written in screenplay format. But maybe I should take a course at NYU first before I commit.

What are you working on currently?

I’m currently working on my second book, a Gothic academic novel. I’m having a lot of fun with it—channeling all my rage at what has happened to academia in general and what, more specifically, went down at my former place of employment last year before I left. But mostly I’m having fun with the Gothic genre. I taught Gothic literature and film for so long that it’s exciting to try my hand at it. I’m aiming for what all those folks I listed above do—using the conventions while twisting them into something new.

What are you reading right now?

I’m always reading one book and listening to another. Right now, I’m reading (and very much enjoying) Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Long Island Compromise and listening to Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women. I’m also making my way, very slowly, through William Serrin’s Homestead: The Glory and Tragedy of an American Steel Town as research for my current novel, which is a flavor of Gothic that might be called “Rustbelt.”

MEG TOTH is a fiction writer and an Assistant Editor/Reader for Conjunctions Magazine. Her short fiction, which has appeared or is forthcoming in such venues as the Idaho Review, Pithead Chapel, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet (Kelly Link & Gavin Grant), and Barrelhouse was nominated for the 2025 & 2024 Pushcart Prize the 2024 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. She lives in New York City, where she taught college film and literature courses for over a decade, but she was born in Cleveland, and Ohio—and the Midwest more generally—appears frequently in her writing. That said, she is currently querying her debut novel set in near-future Hollywood. Toth has received residencies from the Ragdale Foundation and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts to work on her second novel, a Gothic campus thriller.