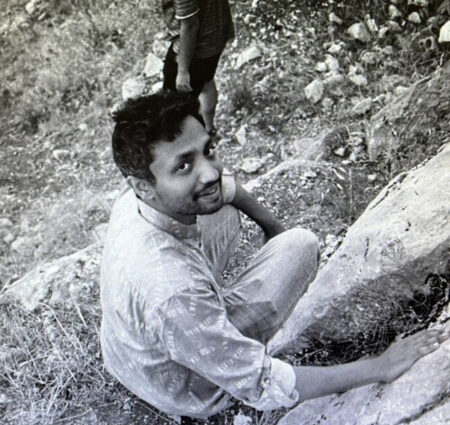

10 Questions for S. Shreyas

This essay was first prepared as a talk on caste, class, and race for the third annual Association of Postcolonial Thought symposium at UMass Amherst. As an ethnographer, I planned to draw on the work I have done in the city I have loved every day of my life, a place that has possessed by “interior landscape,” to use A. K. Ramanujan’s words: Bangalore.

—from S. Shreyas’ “Four Glimmers of Ambedkar’s ‘Fraternity,'” Volume 66 Issue 1 (Spring 2025)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you wrote.

I cannot remember. But I do recollect, quite vividly, my early encounters with the written word. Growing up, writing meant inscribing someone else’s letters, copying them down faithfully. My parents took my hand and traced my first letters on a bed of rice, as was the tradition in South India. The message was clear: ‘from here on out, your ability to eat is tied to these letters.’ It was a terrifying, wonderous, and most importantly, tactile introduction to literacy.

In school, we practiced our alphabets on little, handheld chalkboards. We faithfully traced our teacher’s handwriting, in English and Kannada. I still remember touching and smelling the chalk, being transfixed by the teacher as she carved out fluid shapes on a fresh, black surface. I remember the trouble we took preserve our homework. One wrong move and the chalk would rub off on your school uniform. Our teachers looked for any excuse to give us ‘a tight slap’. Corporal punishment was still the order of the day. We held our boards at a safe distance as we walked to school. We placed them on a pedestal as we played cricket. To make matters more treacherous, I turned out to be lefthanded.

Later, our teachers dictated lessons, in history or literature classes, that we transcribed word for word in our notebooks. We were assessed for spelling mistakes as well as handwriting. At some point, the school asked us to write in cursive using fountain pens. We were ecstatic. The stationery shops buzzed with activity. Our families, many of modest means, spent liberally to buy us what we needed. We compared pens and inks, bemoaned leaks and blots. There were fierce competitions to be the fastest, most elegant scribe. I had a good hand, but I buckled under pressure.

This was my literary background before migrating to the U.S. So, I was perplexed when my American public school teacher asked me to write a book report on a topic of my choosing. This was my first piece of writing.

For a long time, I cherished this memory as my first act of free thinking. Now, I relate to it with some ambivalence. My handwriting soured, as did my spelling. Soon, I was forced to type on a screen, a form of writing I still find alienating. Many American freedoms are born of conquest, and for this reason, contain an element of pretense. Some of my first American friends came to school hungry, others struggled to grip a pen. But for the American public, hunger and illiteracy remain foreign problems, not domestic threats. In America, students are often taught to delink writing from matters of the stomach. I believe this breeds new forms of hunger, new forms of illiteracy, and new false freedoms.

I wanted to write about this. But I did not have the wherewithal. So, I produced a book report in my neatest handwriting. I remember consulting the Merriam-Webster dictionary to faithfully reproduce the American spellings. I received a B+.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

Mahasweta Devi’s Imaginary Maps, C.L.R James’ Beyond a Boundary, Edward Said’s Reflections on Exile, E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, the essays of A.K. Ramanujan and D.R. Nagaraj, and the first four volumes of Subaltern Studies.

Close to my heart are the writings of Du Saraswathi, K.B. Siddaiah, Gogu Shyamala, Devanuru Mahadeva, and K. Ramaiah. English readers can find a selection of their work translated in Steel Nibs are Sprouting, a remarkable volumeedited by K. Satyanarayana and Susie Tharu.

What did you want to be when you were young?

A bus driver employed by the K.S.R.T.C, the public transport system run by the government of Karnataka. These were days before power steering, and I derived tremendous pleasure watching the driver shift gears and rotate the steering wheel. I thought it was the most heroic vocation, to move a bus load of people up and down the Western Ghats.

Recently, the state government passed a law that enables adult women to ride these buses free of charge. It has transformed the lives of working and rural women.

What inspired you to write this piece?

The state of the world, those profound encounters one has as an anthropologist conducting fieldwork, and the indispensable thought of B.R. Ambedkar.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

Bangalore, rural Karnataka, the interior landscapes of 12th century Lingayat mystics. Amir Khusrau’s Delhi.

Is there any specific music that aids you through the writing or editing process?

I listen to Qawwali: Farid Ayaz and Abu Muhammad, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Rizwan Muazzam Qawwal. Or I listen to Hindustani classical music.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

I choose a poem, usually a medieval Kannada vachana, and attempt an English translation. It usually unlocks a door beyond our capitalist present.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

My life companion Sasha. Then, my two best friends. After that, my parents.

What are you working on currently?

An ethnography of sanitation work in Bangalore.

What are you reading right now?

A translation of Kabir verses by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra. And I eagerly wait for my copy of Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp, which just won the Booker.

S. SHREYAS teaches anthropology at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, ME.