10 Questions for Margaree Little

***

My goldfinch, I’ll throw back my head—

let’s look at the world together:

A winter’s day, prickly as chaff,

isn’t it hard on your eyes?

—from The Voronezh Notebooks by Osip Mandelstam, translated by Margaree Little, Volume 66 issue 3 (Fall 2025)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

One of the first pieces I translated was a love poem by Marina Tsvetaeva, in which the speaker questions why she feels “such tenderness” for her lover, having known others before him. Although the lover is not named, the poem is understood to have been written for Osip Mandelstam, in the context of the brief relationship Tsvetaeva and Mandelstam had in 1916. One of the identifying markers in the poem is the speaker’s reference to her lover’s “eyelashes” which are “longer than anyone’s.” Mandelstam had remarkably long eyelashes, a feature of which, Nadezhda Mandelstam writes in her memoirs, he was often embarrassed.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

Dickinson has had a profound influence on my writing, as have contemporary poets Layli Long Soldier, Robin Coste Lewis, and Monica Ong. Writers of faith and doubt—Hopkins, Herbert, Simone Weil—are also lasting influences. Translating and being immersed in Russian-language poetry, specifically Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva, have impacted my writing and how I think about poetry in ways I couldn’t have imagined. Image, music, feeling, and meaning coexist in their work in ways that are quite different from what we find in much American poetry.

What other professions have you worked in?

Before I began teaching, my background was primarily in social justice work, including with a sister-city project in the West Bank of Palestine and in immigrant rights organizing. When I first moved to Tucson, I worked for for No More Deaths/ No Más Muertes, a humanitarian aid organization on the U.S./ Mexico Border. I coordinated a project to document Border Patrol abuse, working in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, and in the Sonoran Desert. My first book of poetry, REST (Four Way Books, 2018) emerged out of these experiences. During this time, I did a range of other things to make ends meet, including caregiving and cleaning houses. I have also worked on farms in Maine and Arizona, at a domestic violence shelter, and as a reading tutor at the public library in Tucson.

What did you want to be when you were young?

When I was young, I didn’t know that one could “be” a writer in the sense of a career. (And I’m still not sure about this.) I wrote and read because I needed to, and because it kept me alive in very difficult circumstances.

What drew you to translate this piece in particular?

Mandelstam’s goldfinch poems belong to what are known as his Voronezh Notebooks. Arrested in 1934 for writing a poem on Stalin and tortured in the Lubyanka, Mandelstam was then sent with his wife, Nadezhda, into exile in Voronezh, a city close to the Ukrainian border, where they spent the next three years. In many ways, this time was unimaginably hard for the Mandelstams; they lived in poverty and almost complete isolation, and always with the underlying intimation that his first arrest would not be his last. Yet during this time, Mandelstam wrote an astonishing sequence of poems, in which the goldfinch becomes an embodiment of beauty and the resilience of life. I love the poems for the sense of internal freedom they convey.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

I don’t think there is one location that influences my writing, but I do think my poems are autochthonous, in the sense that they always emerge out of a specific place, whether that place exists for me in the present or in memory. When translating, I suppose I am always trying to imaginatively inhabit the world in which the original poems came into existence.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write?

Over the last years, I have begun to see poetry less as a process of production (an outlook toward which I think we are often trained in graduate school) and more as a process with its own organic ebbs and flows that I need to respect. So, I don’t do particular things in order to write. But on the other hand, I do think we need to show up and be present if and when poems arrive, and for this, it helps me to get up early, before the day is underway with its many external demands.

Who typically gets the first read of your work?

My spouse, the poet and translator Rebecca Seiferle.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I have always been interested in visual art, and over the last nine years I have done more work related to this, especially in pen and ink and watercolor drawings. This has included two illustrated children’s books, but so far, these have just been for me. I would like to continue to develop this work, and one day be able to share it more broadly.

What are you reading right now?

I recently finished Mikhail Bulgakov’s 1920s satirical novella Heart of a Dog and am working through a book on Russian morphology and roots. My reading list for the fall includes Cole Swensen’s translation of Pascalle Monnier’s Touché, Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad, and Toni Morrison’s collection of essays, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination.

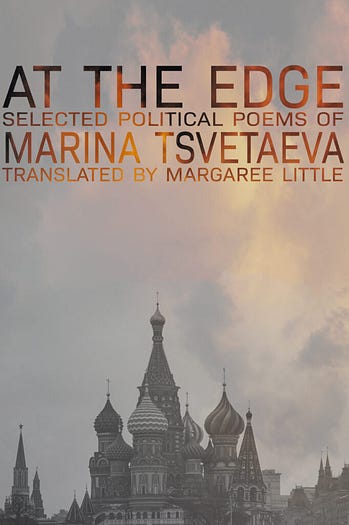

MARGAREE LITTLE is the author of Rest (Four Way Books, 2018), winter of the Balcones Poetry Prize and the Audre Lorde Award. Her translation At the Edge: Selected Political Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva is an Editor’s Selection from Green Linden Press, forthcoming in November 2025. Her translations from the Russian of Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva appear in American Poetry Review, Asymptote, The Michigan Quarterly Review, Solstice, and The Brooklyn Rail (InTranslation); her critical writing on translating Mandelstam has been featured in APR and Asymptote. She is the recipient of awards, fellowships, and residencies from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, the Kenyon Review, Bread Loaf, the Camargo Foundation, and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig, among others. She lives in Tucson.