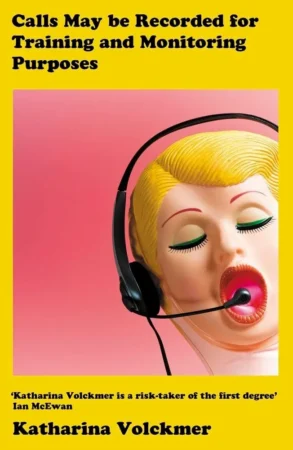

A Review of Katharina Volckmer’s Calls May Be Recorded

Katharina Volckmer’s second novel, Calls May Be Recorded (Two Dollar Radio, 9/16/25) is a fierce workplace satire that is bold in its exacting focus on those pushed to the margins of this century’s rapidly shifting labor market. It follows the protagonist Jimmie on a tragicomic gambol through a single day at a London call center. Jimmie works the evening shift at Vanilla Travels Ltd., fielding complaints from unhappy vacationers, people “at odds with their own hedonism.” He spends the first half of his shift under the watchful eye of his (younger) boss Simon, surrounded by a multinational ensemble cast of misfits, and the second half alone at his desk pod, occasionally harassed by a menacing Portuguese janitor.

Jimmie is thirty, gay, single, an Italian immigrant living with his emotionally distant mother, and working a job he hates. He’s in love with his married coworker, Daniel—who just got promoted—and infatuated with Simon, who is also married. Things only get worse from here, as Jimmie soon has reason to believe he’ll soon be fired for giving Daniel a blowjob in the employee bathroom on the previous Friday.

Jimmie’s darkly humorous decline is punctuated by a series of bizarre customer complaints that he must respond to with as much empathy and professionalism as he can muster, which often amounts to very little. Whenever he has a spare moment, Jimmie grapples with a constellation of personal issues—his weight, his mother, his finances, his confusing desires, his job, of course—while navigating a complex set of workplace dynamics that foreground the absurdity of making a living in the 21st Century. Jimmie is a keen observer of his surroundings, but his analysis is focused on past moments of trauma.

Volckmer’s swerving associations, the images and notions her narrator lands on and emphasizes—a kind of visual syncopation—take a bit of getting used to. Calls May Be Recorded defies easy categorization as it derives its narrative pulse from both stream-of-consciousness and a traditional plot structure. The second paragraph, unflinching, with its cascade of details that somehow retain their granularity, showcases Volckmer’s associative virtuosity:

Jimmie looked at the expensive dogs and babies on the bus he was taking into work, wondering whether they were all fitted with special nappies that would immediately alert their owners in the event of a disgrace. Shielding them from our primordial fear of excrement and the diseases it carries, the fear we feel for our bodies. The instinct that tells us that this is far worse than wetting your bed, that no childhood trauma will ever be endearing enough to justify those brown stains. Because those stains are for old and damaged people in care homes, or the people Jimmie would sometimes see on this bus route. Bodies that had lost the fight with their own fluids, one step away from ultimate misery.

Here, Volckmer lays out the stakes for the entire novel. Calls May Be Recorded is deeply concerned with the question of what to do with our bodies and desires in the workplace. It explores the urges toward sex, defecation, and love, sometimes blurring the lines between them. The final sentence deftly tees up Jimmie’s past job at the funeral parlor, and by extension, the inciting incident that set the novel’s present action into motion. Hint: the event involved a corpse, his mother’s maternity dress, and shit.

Calls May Be Recorded is rife with dark humor, much of it sharp and very funny. After being scolded by his pod mate Wolf, an uptight German, for making a sex joke:

Jimmy knew that they had a zero tolerance policy for all human urges and that according to their official handbook it was best to not have a body at all, to simply exist as an immaterial being that worked hard and didn’t suffer from any kind of pain or longing.

Like much of the prose that fills the brief novel’s 127 pages, this passage does double duty. Here, Volckmer comically exaggerates the cold legalese typical of employee handbooks, but she’s also making a more subtle and specific point about what it really means to work in a call center. To the entitled, often wealthy vacationers who call in with complaints, Wolf and Jimmie are formless, mere voices stripped of all personality, betraying no desire beyond the need to solve the customer’s problem.

When Jimmie isn’t answering phone calls or escaping to the bathroom, he mostly thinks about his mother, “the Signora.” Throughout most of the novel, Jimmie expresses nothing but resentment and jealousy toward her. She is the reason he lost his job at the funeral parlor, the reason his cat ran away, and the reason he’s stuck in London.

And yet, Jimmie enters the call center wearing the Signora’s red lipstick. A passing familiarity with Volckmer’s excellent first novel, The Appointment, would be helpful in contextualizing this choice. The narrator of The Appointment is a German woman, and the novel consists entirely of an extended, confessional monologue to her Jewish physician. With the assurance of doctor-patient confidentiality, she details her psychosexual preoccupation with Hitler, along with the various shames brought on by her nationality, her gender, her desires, and her past relationships.

If The Appointment is Volckmer’s attempt to confront the individual’s inheritance of national shame, Calls May Be Recorded does similar work at a more intimate level. In neither book does the author beat around the bush. To Volckmer, perhaps, identifying the source of shame is the easy part. All we need to do is know our history and know ourselves. The challenge she sets for her protagonists is to integrate their shame into their identity in a way that allows them to achieve some degree of self-actualization, or at least enough moments of contentment to string together a semblance of a decent life. As Jimmie tells his coworker Elin toward the end of Calls May Be Recorded, “The only real revolution is to be happy in spite of your circumstances.”

The novel’s long central section, “A Day,” is followed by a brief epilogue titled “A Variation,” but is this an alternate ending, or a coda that reveals how the final, cathartic moments of “A Day” shift Jimmie’s mood and cast of mind, a kind of post-credits teaser? Instead of encountering yet another caller “at odds with their hedonism,” the man on the other end of the line is just looking for companionship. This caller seems to recognize what Jimmie has been telling his customers all along: you can’t escape your personal problems or the histories you inherit—not even in paradise.

Calls May Be Recorded is a slim volume, but it doesn’t feel brief. Jimmie’s physical freedom is restricted, but his mind wanders. A few flashbacks notwithstanding, the reader’s imagination is restricted by the walls of the call center. The book is quite dialogue-heavy, but the middle still manages to drag. Perhaps, by hemming her protagonist in so tightly, Volckmer invites the reader to experience, on some level, a taste of Vanilla Travels Ltd.’s exhausting monotony. But once you lose a reader, it can be tough to get them back. And unlike Jimmie, the reader can quit whenever they want.

Katharina Volckmer’s second novel is perhaps more original than her first, though less daring in its social critique. The scatological references and ironic tone that pervade Calls May Be Recorded highlight the sense of precarity that many workers experience every day in today’s economy. Jimmie learns that possessing a college degree does not guarantee gainful employment, and that a single slip-up in the workplace can derail one’s life for years. In this way, the novel presages fresh concerns around how technology, particularly AI, may impact the labor market in the months and years to come. Calls May Be Recorded also reminds readers that, despite the efforts of governments and corporations to reduce each of us to an algorithmically legible dataset that can be profited from and controlled, people remain messy, chaotic, and very often disgusting. We screw up. Occasionally, we shit our pants. We can find meaning in anything: a blowjob, a bathroom stall, an electric carving knife, our mother’s lipstick. Our minds make them beautiful, essential.

Christopher Santantasio is a writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. His work can be found in One Story, Story Magazine, DIAGRAM, Pinch, Boulevard, Epiphany Magazine, and elsewhere in print and online. Raised in the Hudson Highlands, he edits fiction at The Rumpus and is at work on his first novel. Find him sometimes here: @crsantastic.bsky.social.