7 Questions for Alton Melvar M. Dapanas and Stefani J. Alvarez-Brüggmann

OUR BARRIO SITS on the borders between Bukidnon province and Cagayan de Oro city, a half-forgotten hinterland. Cross the last sitio’s bridge, and you’ve left the city behind. Bukidnon’s roads are the end of asphalt dreams, where concrete gives way to earth: a bumpy quagmire in the season of rains, a dusty expanse in the summer heat. Towards the city proper, the smooth roads stop at the third barrio, as if someone decided we’d had enough luxury. But in the neighboring barrio of Lumbia, the road is paved anew, perhaps because the city sees its airport as a shrine and therefore, worthy of road projects.

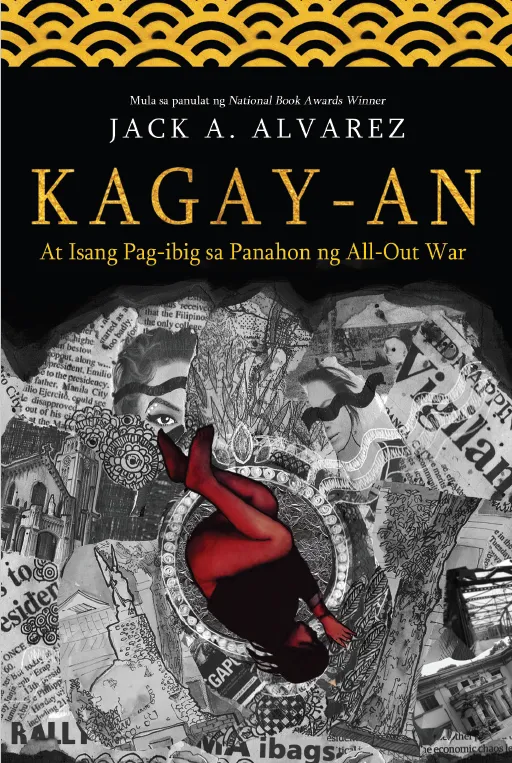

—from Stefani J. Alvarez-Brüggmann’s “Kagay-an and a Love in the Time of an All-Out War,” translated by Alton Melvar M. Dapanas, Volume 66 issue 3 (Fall 2025)

Stefani, could you tell us about an early work that felt significant to you? Alton, what was your introduction to Stefani and her work?

Stefani J. Alvarez-Brüggmann (SB): I consider my first book, Ang Autobiografia ng Ibang Lady Gaga, as my first significant milestone. I actually self-published it back in 2012 before indie press VisPrint picked it up in 2015 and went on to win a National Book Award in the Philippines the year after. I see the book as my coming out into the literary world, the one that opened the door to so many opportunities and achievements. In writing these stories, I found a chorus of voices of my many selves, all that I ever was and all I would ever be, finally connecting with one another, collaborating, contributing, communing.

Alton Melvar M. Dapanas (AMD): I discovered Stefani’s first book in early 2016, hidden in a corner of a bookstore chain that hardly ever featured Filipino authors. Her stories were sobering: being a trans Filipino migrant worker in Saudi Arabia whose economic survival occasionally meant treading into sex work. The real connection clicked when I learned she was from my hometown, Cagayan de Oro. It’s a city without sustained literary infrastructures, so published writers are rare, and published books about the city itself rarer still. This is precisely why translation feels an imperative. Politically, Cagayan de Oro is a southern city where you often feel like an outsider if you don’t support the dominant, right-wing populist regime. Back then, finding Stefani’s book felt like finding a kindred spirit.

We often talk about literary ancestors. Who are yours?

SB: The short stories of Genoveva Edroza-Matute (1915-2009) first enchanted me in grade school. Maybe it was her main characters, mostly teachers and students, who always found a glimmer of hope by the end of each tale. Her writings showed me that stepping into a classroom is one of life’s most meaningful rites of passage, a space where we mirror our own innocence and rediscover the essential lessons of learning and humanity. Years later, when I read her collection Diaspora at Iba Pang Mga Kwento (Diaspora and Other Stories, 2005), it felt like looking into a mirror that still perfectly reflected me. When I got to high school, I discovered the novels of Lualhati Bautista (1945-2023) at a downtown bookshop, the only one in the city at the time. Her subversive prose became my secret confidant. At a time when I was newly aware of the incessant social and ethnopolitical turmoil in the conflict zone that is the Philippine south, Lualhati’s writings gave voice to everything I was feeling while coming of age in the ‘90s.

AMD: I’ve long been drawn to works that blur the lines of genre: Anne Carson, Dionne Brand, Maria Stepanova, Judith Schalansky, Maggie Nelson, Yoko Tawada, McKenzie Wark, Sara Ahmed, Julietta Singh. (Locally, I’ve always adored the writings of essayist Wilfredo Pascual and poet Conchitina Cruz.) As a translator, I’m naturally drawn to this same spirit, which I find in the works of Stefani.

Let’s talk about Stefani’s autofictional novella, Kagay-an and a Love in the Time of an All-out War, an excerpt of which appears in MR 66.3. What drove you to (Stefani) write and (Alton) translate this story?

SB: Writing Kagay-an at Isang Pag-ibig sa Panahon ng All-out War meant wanting to unearth the emotional depths of my childhood, and the despair of that time, as I remembered them in my senses. To begin remapping each chapter of my past, I have to return to the place itself. It’s only there that I can truly feel, in every fiber of my being, that the body never really forgets.

AMD: Translating Kagay-an and a Love in the Time of an All-out War, shortlisted at the National Book Awards in the Philippines in 2019, felt more urgent than Stefani’s other work for a couple of reasons. First, I’m also from Cagayan de Oro, the setting (and in so many ways, a character) of this novella. It’s a place we don’t see often in published literature, so that felt personally significant. More than that, I need a real connection to the work I translate—and I did! I don’t have to be friends with the author I’m translating, but I absolutely have to believe in their creative vision and where they’re headed. I have to trust in the expanse of their work, both now and in the future.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

SB: Call it faith, but no matter where I and my pen end up in a distant land, or if I find myself writing in another foreign tongue, or even if all of this fade into daydreams, my sanctuary will always be Cagayan de Oro. It’s here that all my dreaming will come home to rest.

AMD: I have to say, it’s less on the place and more on the memory of the place. My first and third books were haunted by solastalgic versions of home, Cagayan de Oro city and Misamis Oriental province, that lives only in my imagination now. Perhaps places that may have never existed outside of my head.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to write or translate?

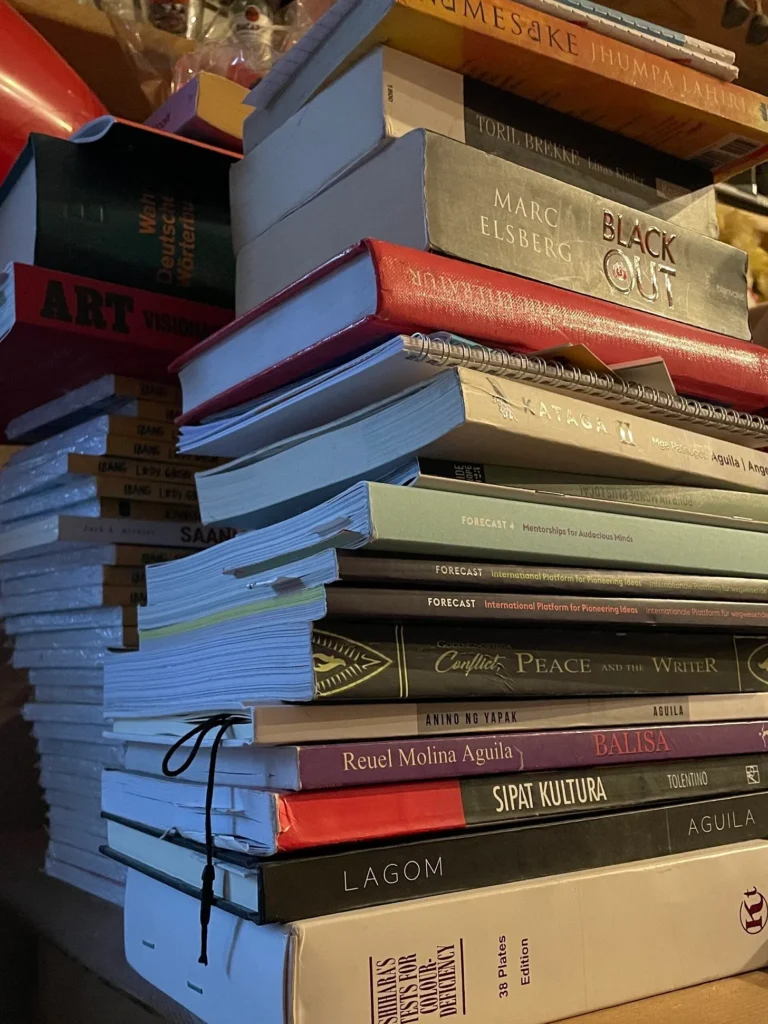

SB: I can’t help but drift off into thought whenever I’m walking, riding public transport, or revisiting familiar spots. I know my territory well like a cat: every detail, every familiar face, they’re all clear even behind closed eyes. I’ve always been drawn to bookstores and libraries. Sometimes I quietly organize the books, other times I skim through pages at random, reading bits and pieces until I wear myself out. This often leads me to doze off at home, only to wake up in the deep, quiet hours of the night, moments before daybreak.

AMD: My little writing ritual is getting into ancient astrology, which I owe to a Tinder date who was super into the occult. I’m not talking about those New Age horoscopes you see all over TikTok and YouTube. I mean the ancient texts from at least a millennium ago like Ptolemy’s Tetrabilos, Vettius Valens’ Anthologia, Abu Ma‘shar’s Kitāb al-mudkhal, and Firmicus’s Mathesis. It’s like my secret weapon for getting into the creative zone. A day-long hike along a mountain, or a lazy stretch on the beach with a bottle of wine and plenty of shīshah never hurt, either.

What are you both working on currently?

SB: I currently have a couple of ongoing writing projects that I’m excited about: the epistolary Transfinity Diary and the mythopoetic Siyam Napu’t Siyam na Ngalang Pinakamamahal Ko (The Ninety-Nine Names of Those I Love the Most). Lately, a significant part of my creative energy has been devoted to expanding my flagship outreach initiative, The Other Lady Gaga (TOLG) Project. At the heart of TOLG is a creative writing workshop series we’ve named “Sandagling Talakayan,” a portmanteau of “sandali” (brief) and “dagli” (a Filipino short prose genre I’m known for), combined with “talakayan” (craft talks). As an homage to the student editors of the campus newspaper of my alma mater, Mambuaya National High School, I adopted the term for this umbrella project designed for public grade school and high school students. It has been incredibly rewarding to see TOLG grow as we’ve now reached numerous public schools in the city, with hundreds of student journalists and their teachers having participated.

AMD: These days, I’m busy translating Stefani’s Filipino-language prose from several of her books, as well as ecofeminist poet Cindy A. Velasquez’s Lawas (Body, 2016) originally written in our Cebuano Binisaya native-tongue. Somehow, in between that, editorial duties, and pitching to agents and publishers, I’m volunteering for literary initiatives supporting Palestinian causes and slowly piecing together what I hope will be my next book of lyric essays. I’m also starting to gear up for a mentorship lab for emerging Mindanaoan writers I’d like to launch in the next few years, something like a “Field Guide to International Publishing.” It’s a niche I’m uniquely qualified to teach at the local level.

What are you reading right now?

SB: I finished The Birchbark House by Native American novelist Louise Erdrich just last week, but it’s not a story you simply put down. I found myself picking it up again, reliving the plot, and being drawn back into its storytelling. It’s become my favorite companion for visits to my father’s grave. Closing the book for the first time, I wrote:

…returning to you, I whisper the end of Omakayas’s tale. How she murmured to herself that she has a good family, and then held her doll, one of her most cherished things. This moment, I will not forget. I record then, I record still, wherever I may find myself. I will follow the slow turn of seasons, summer, autumn, winter, and spring. In their rhythm, my memory will drift, as you said it would. Into the earth, I will bury what remains.

AMD: My reading habits are joyfully chaotic, like a browser with a hundred tabs left open. My current stack includes Li Zi Shu’s Gàobié de niándài (trans. YZ Chin), Betsy Fagin’s Fires Seen from Space, Maria Borio’s Trasparenza (trans. Danielle Pieratti), Ahmad Almallah’s Bitter English, and Irizelma Robles’ El libro de los conjuros (trans. Roque Raquel Salas Rivera). Beyond literature, I’m reading a book of planetary omens from ancient Babylon. So six books at once, just as Virginia Woolf intended!

Stefani J. Alvarez-Brüggmann (she/her) is an alumna writer-in-residence at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany. A trans migrant worker-activist, she lived in Jubail and Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia from 2008 to 2022. Her short prose collection Ang Autobiografia ng Ibang Lady Gaga (VisPrint, 2015) won at the National Book Awards in the Philippines, while her autobiographical novella Kagay-an at Isang Pag-Ibig sa Panahon ng All-out War (Psicom, 2018) was a finalist. Stefani’s works have been featured in magazines, small press fairs, anthologies, book festivals, and art exhibits in New York, Beirut, London, Taipei, Chicago, Helsinki, Berlin, Macau, Paris, Dublin, Beijing, and elsewhere. She divides her time between Würzburg, Germany, and her hometown of Cagayan de Oro in the southern Philippines. Visit her website at https://stefanijalvarez.com.

Alton Melvar M. Dapanas (they/them) is an essayist, poet, and translator from the southern Philippines. Author of three books of lyric essays and prose-poems, including M of the Southern Downpours (Australia: Downingfield Press, 2024) and In the Name of the Body: Lyric Essays (Canada: Wrong Publishing, 2023), their works have been published globally, from South Africa to Japan, France to Singapore, and translated into Chinese, Damiá, and Swedish. They’ve been published in World Literature Today, BBC Radio 4, Michigan Quarterly Review, and the anthologies Infinite Constellations (University of Alabama Press) and He, She, They, Us: Queer Poems (Macmillan UK). Formerly with Creative Nonfiction magazine, they were nominated twice to the Pushcart Prize for their lyric essays. Find more at https://linktr.ee/samdapanas.