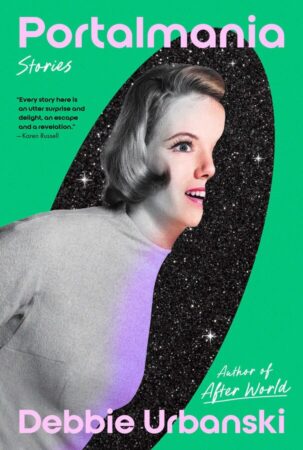

Where Does It Lead? A Review of Debbie Urbanski’s Portalmania

“I think it’s time to question what we ask of authors, particularly new authors, in exchange for

paying attention to them,” Portalmania author Debbie Urbanski wrote in a recent LitHub article,

raising important questions about personal boundaries in the context of book marketing, that

icky blood ritual of churning out social media posts, podcast interviews about personal traumas,

and, of course, placing book reviews that entice without pandering. But Urbanski also speaks to

a greater cultural desire for omniscience, a desire undoubtedly linked to the siren call of

technology and the digital world we all have laying beside us or sitting in our pocket at this very

moment. Now that we can find answers to almost any question in minutes if not seconds, what

are modern audiences around the world to do with the age-old question, ‘What do we do with the anxiety of not knowing what all this is about? And what if we don’t actually like this world and want to go somewhere else?’

Like the title of this collection of short stories suggests, Portalmania obsesses over portals, both

as metaphor for transformation and as a phenomenological entity. Urbanski stretches this

fascination over nine stories filled with child abductors, medical anomalies, space travel, and

even an America with two presidents (one for the even days and one for the odd), taking the

reader in creative and intriguing directions that mirror our ‘real’ world while carefully avoiding flat

allegory. Her stories are sci-fi, surrealist, speculative, and whatever Frankenstein genres a

book-tokker might conjure up, each plot a collision-course between the portals themselves and

the quotidian lives of the characters as they navigate feelings of anxiety and uncertainty in their

relationships.

Urbanski’s characters are seeking both a way out and a way through their individual

predicaments. In “How to Kiss a Hojacki,” Michael and his wife work through marital conflicts

that intensify when she finds herself becoming one of the Wonderfuls, a group of women

displaying a range of symptoms including blue skin, mutism, and a complete “repulsion to sex

with any gender”(23). Set against a governor’s race hinging on the social question of what to do

with these Wonderfuls, we see them engage in a kind of couple’s counseling–Michael struggles

to see himself in relation to his wife’s new identity and to understand the terms he had always

assumed he knew–terms like sex, wife, and love–as redefined by these new circumstances,

while his wife finds a new form of autonomous speech in Post-its. This is the choice that many

of Urbanski’s characters face: to pass through a portal to that unknown where either growth or

destruction awaits, or to sit and spin in stagnation.

But it always comes down to choice, really, between being taken by anger or frustration in these

new circumstances or accepting them. In the first story, “Promise of a Portal,” we are introduced

to the portal creepers, a group of women-driven vans that abduct predesignated girls, who are

eventually returned appearing visibly and emotionally changed for the worse. The story’s

protagonist yearns to join them, to be seen as selectable, even at the risk of experiencing what

we can assume is a type of sexual molestation. As the protagonist grows older, marries and

divorces, that despondence turns into disassociation: “People kept expecting someone different

in my place. If I spoke using my own voice, or acted naturally, acting like who I was, a tangible

sense of disappointment overtook the room, like an acidic smell in the air.” (8)

Taken together, the protagonists of these stories express, in their own unique ways, the

discomfort of being perceived. The modern Here that they inhabit itches at their body

and psyche equally, like an uncomfortable sweater, so that they become more and more aware

of that happy-smile mask so many of us put on to ward off the inescapable brutality of the real world. What Urbanski is grappling with in these stories is a seduction ideation, a perseverating

over the ways our world bends us toward its recklessness, and the various gateways that can

appear out of thin air with a promise only of being somewhere different.

Because that is ultimately what makes the stories of Portalmania so enjoyable, each offering an

entry to another world where the characters are doing the same things we are with the

circumstances in which they live, like the protagonist from “Long May My Land Be Bright,” where

America has compromised with an Even and Odd day president and rifts of light have begun to

spring up across the country. Like the protagonist, we find ourselves in a world where division

and uncertain futures are all we know, it seems, and the various knowledges (and knowledge-

makers) bearing down on us have elevated our collective dread. But that’s where good fiction

comes in, when the only thing we can do is dive in. “Below me I can hear noises, not

necessarily discordant. The scent of charcoal and residue. A faint pink light,” the protagonist

documents before jumping in. “I’ll write more when I emerge” (79).

Ultimately, there’s always something on the other side of the portal, on the other side of the

page, on the other side of the darkness. And, as Urbanski reminds us, when we emerge on the

other side, we will still be there to create.

Edward Clifford is a writer and editor from Massachusetts. His work can be found in Paperbark, Many Nice Donkeys, Press Pause Press, and elsewhere.