Stories from Crisp County

Editor’s Note. When we first read “Night Man,” Bill Pitts‘s contribution to our current issue, we figured the backstory might be as good as the story. So we asked him to tell you about it.

Crisp County’s prison closed in 1975, a few years after I was born, but I have been hearing about it all my life.

My father always told me how his friend Bill Goff, the warden’s son, grew up on the county farm. When Bill was little, the inmates would pull him around the yard in his toy army jeep.

My mother once went to the Goff house to visit Anne, the warden’s daughter, and found her standing in a chair while a uniformed inmate penned up the hem of her dress for the dance.

Bill Goff himself had so many stories that he felt someone should write a book about the camp. My father arranged for us to meet.

“When I was growing up on the county farm,” Bill began, “we had an inmate houseboy named Johnny Clifford West. Johnny could neither read nor write nor even tell time, but he knew the Greyhound bus came by the house every morning at six. He’d watch for it while making breakfast. When he heard it coming he’d knock on Daddy’s door and say, ‘Cap’n, the bus done run.’”

Melvin Clemmons, the walking boss—“That guy in Cool Hand Luke with the mirrored sunglasses would have been the walking boss”—shot a fleeing inmate. Just eight years old, Bill had gathered with the bull gang around the young man’s body while the slow air-raid-like siren of a dilapidated Cadillac hearse—“no ambulance in those days”—wailed in the distance.

Finn, the inmate master cabinet maker, got drunk off banana mash brewed in a bull pen fire extinguisher.

Hamp Morris, the dog boy, took the bloodhounds and a Smith & Wesson revolver into a Moultrie swamp and caught the killer Tom Williams.

“Why was Hamp in prison?” I asked.

It was the first of many questions.

Bill couldn’t remember, but his sister Anne did when we met for lunch a few months later.

“Hamp shot our washer woman’s husband,” she said. “He owed some money and couldn’t pay it. Hamp just took his gun out and shot him.”

Bill’s mother Lillian told me how a troublemaking inmate sketched Christ on the isolation cell wall. She showed me a Polaroid. Jesus is well-drawn, but glaring, angry.

We met with the former inmates Tracy and Willie Henry, who spoke of smuggling marijuana and shanks, of Martin Luther King on the bull pen radio.

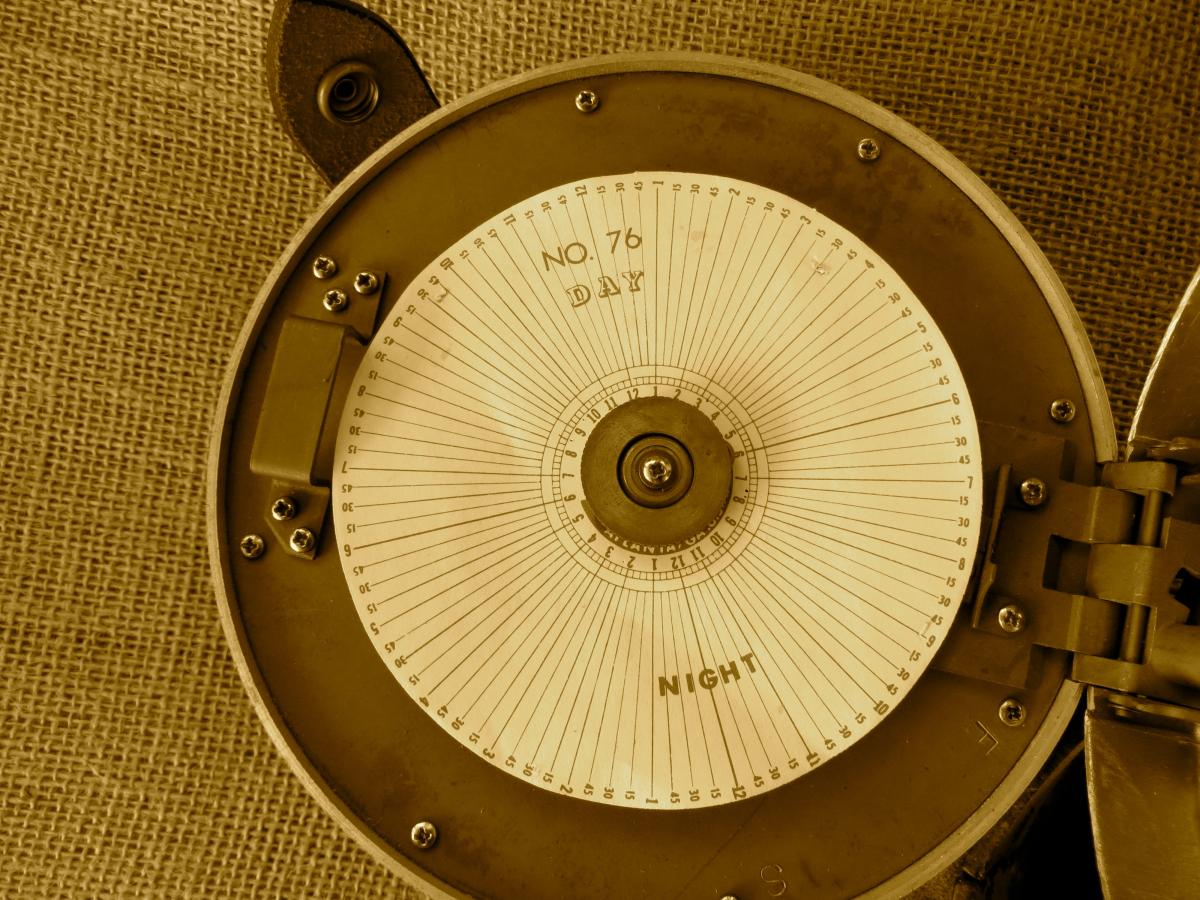

I studied old Board of Corrections reports, a “true” detective magazine, many contemporary newspaper articles. Bill drove me out to the old camp, showed me the crow’s nest where Curtis Clarke the night man used to sit, the time clock he slung over his shoulder when he made his rounds.

Much of what I learned surprised me. Though some inmates did mow the roadsides with sling blades, many others were skilled laborers—heavy equipment operators, mechanics, concrete workers—who paved the roads that made today’s prosperity possible. Though a place for punishment, the camp also provided a refuge for men—inmates, guards, and even the warden—in a society whose ideals of what a man should be often directly contradicted its laws.

The lost world of the camps began to take shape in my mind and, eventually, on paper.

One of the resulting narratives is “Night Man.”