Notes on Web 3.0 (Part One)

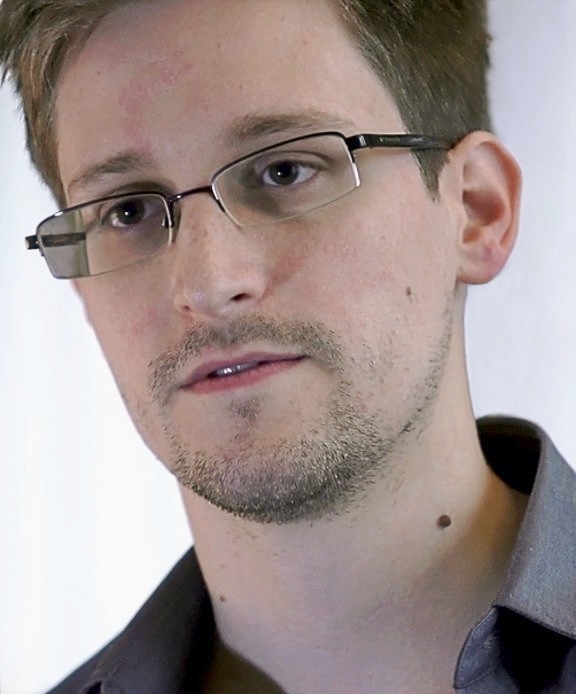

Editor’s Note. In press coverage of the Snowden affair, there often seems to be little sense of what is really at stake. We asked Adam Sitze, from Amherst College’s Department of Law, Jurisprudence, and Social Thought, to shine a bit more light on the subject. What follows here is the first of a five-part series in which Sitze outlines a totalitarian dream, now become our common reality.

The public response to the disclosures made by Edward Snowden in late June has so far assumed a form that is curiously oblique. Far too many commentators on Snowden’s disclosures have allowed voyeuristic and even prurient interest in Snowden’s person eclipse serious thought about the substance of the disclosures themselves.

Other commentators seem to have concluded that the programs revealed by Snowden present no new dilemma at all, and in fact illustrate nothing more than the enduring need for contemporary society to find some sort of balance in the “trade-off” between personal liberty and national security. A few observers, almost despite themselves, seem to have recognized that Snowden’s actions require us to pose questions about the essence and basis of disobedience, about the implicit paradigms that govern our understanding of what disobedience is and should be, about the sources of conscience and its relation to law, about the range of actions that are appropriate for those in whom the voice of conscience speaks in the imperative. But even this last response, by far the most potentially interesting, sidesteps the central problem posed to us by this affair: the sense in which Snowden’s disclosures oblige us to mark a turning-point in the genealogy of the Internet, and thus too, because the Internet is the central mode in which the public mediates its self-relation today, a turning-point in the very concept of the public itself.

1969: The Ur-Scene

It’s well-known, or at least should be, that the groundwork for today’s web of data communications originated in the military research of the 1960s. In the late 1960s, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), together with the RAND Corporation, began funding the research and development of new techniques of computer networking, with the aim of creating a system of command, control, and communication so flexible and decentralized that it could withstand a successful enemy attack on any one of its nodes (up to and including nuclear attack). One result of this research was a technique of data management called “packet-switching,” which allows one user of a communications system to send information simultaneously to multiple other users through variable routes.

This technique was first operationalized in 1969, through a DoD-funded university computer system called ARPANET (“Advanced Research Projects Agency Network”), which is widely recognized as the “backbone” of the global Internet in its contemporary form. The network that seems so normal a part of everyday life today was, in other words, called into being with reference to a scenario that was anything but normal: that the apparatus of the state (and above all, as one of ARPANET’s founding figures argued, the capitalist economy) can and should survive an attack that much or even most of the state’s civilian populations would not survive.

From this perspective, the Internet can’t be interpreted just as a device for the communication of information. It’s also, perhaps even primarily, a military technology that owes its basic structure—characterized by decentralization, sharing, and distribution—to a set of a strategic preparations for a terrible war that was felt to be an inevitability. Conflict of the worst kind, we might then say, is hard-wired into the very shape of the network itself.

If today this origin of the Internet is forgotten (and even, by some, disavowed), it’s because much of the language we now use to describe the contemporary internet is the distant cousin of a very different 1969: that of sixties counterculture. This was a culture that, in its most politicized iterations, sought to “stick it to the Man” and to avoid “the Establishment.” Far from being at home with military power, it resisted the draft, protested ROTC on college campuses, embraced the peace movement, and opposed the Vietnam War. In its more New Agey declension, it strove for “self-fulfillment,” for a unification of mind, body, nature, and spirit, and it fashioned a lexicon for its project from a watered-down portmanteau of “Eastern” religions.

In the early 1980s, its energies all but exhausted, this counterculture found an afterlife in Stanford technophilia. With the long strange trip that connected Haight and Ashbury with Palo Alto, Silicon Valley subculture was born. Known for its intense competition, supremely self-assured entrepreneurs, and plentiful DoD funding, Silicon Valley is also defined by a dogmatically optimistic belief, a naive faith bordering on theology, that cybernetic technology has almost miraculous redemptive and salvational qualities, that it is the obvious and inevitable shape of humanity’s future, that it can solve most problems known to man (and even some that aren’t). Nowhere is this strange brew of high technology, cowboy-capitalism, countercultural iconoclasm, and New Agey mysticism better exemplified than in the corporate person of Apple Computers, sometimes said to be the most valuable company in history. From the beginning, Apple marketed itself in an unapologetically countercultural tone, announcing its intentions in a famous 1984 commercial depicting a woman smashing a screen bearing the visage of “Big Brother,” which it followed up with its less famous, yet even more countercultural, “Think Different” campaign. In the Apple of today, this tone is muted but still perceptible. Its products aspire to a Zen-like simplicity, its luminous, glass stores resemble stylized Hindu ashrams, and its late chairman conducted himself in the mode of an ascetic, visionary guru.

Within the horizon of this 1969, the technology introduced that same year by the DoD would take on a sense very different from its origins in national defense strategy. Packet-switching was here more than just a means to the end of allowing state and economic infrastructure to survive a terrible war. It was a means to the end of iconoclastic freedom and unbounded personal self-expression, a technique for breaking down walls and disrupting existing institutions, a path to a new world of robust dispersion and richly multiple communities. The dawn that motivated it was not the charred, post-apocalyptic wasteland of “the day after”; it was the messianic inception of a crowned anarchy of individuals who were flourishing, interconnected, sharing, and self-fulfilled. In Silicon Valley, packet-switching would be more than just a new technique for transmitting data. It would become the nucleus of a social movement.

To be continued . . .