Notes on Web 3.0 (Part Two)

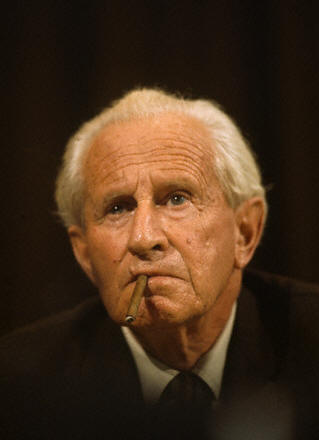

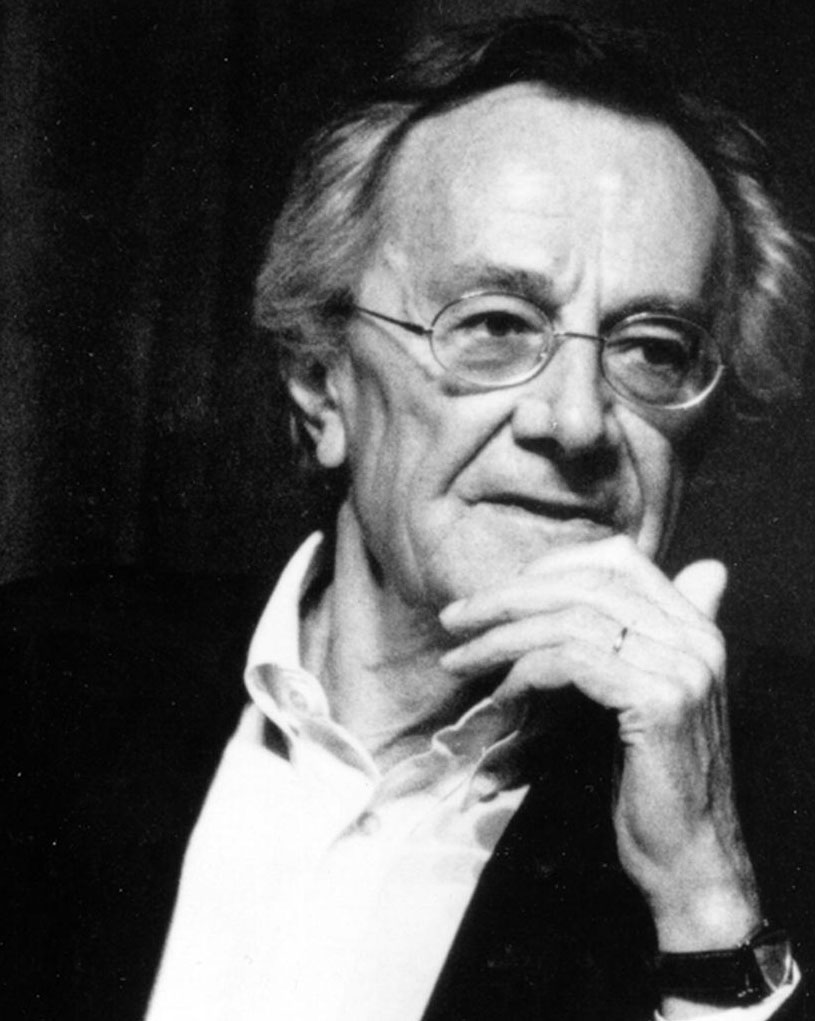

Editor’s Note. In press coverage of the Snowden affair, there often seems to be little sense of what is really at stake. We asked Adam Sitze, from Amherst College’s Department of Law, Jurisprudence, and Social Thought, to shine a bit more light on the subject. What follows here is the second of a five-part series in which Sitze outlines a totalitarian dream, now become our common reality.

Web 2.0: An Unstable Equilibrium

By the late 1980s, the Internet “social movement” slowly began to gain traction and momentum. With the replacement of ARPANET by NSFNet, the transfer of the military’s network technology to civil society seemed to be definitive and complete. With the release of the World Wide Web in 1993, the appearance of browsers like Mosaic and Netscape, and the migration of email from colleges and universities to the general public, Silicon Valley subculture began to determine the shape and tone of public culture more generally. The initial iteration of the Internet—call it Web 1.0—functioned primarily to instruct and to inform, to make knowledge widely and instantly available, to connect researchers with one another and to allow them to broadcast their findings to the public. Over the course of the 1990s, however, a series of technical and social innovations began to alter Web 1.0 from within. The emergence of blogging software, the improvement of search engines, the digitization not only of text but also of sound and image, the proliferation of handheld devices, the appearance of so-called “social media”—all of this seemed to transform the Internet from a one-way street for the dissemination of information from elites to masses into a leveling apparatus characterized by interaction, connectivity, and even community.

At its best, Web 2.0 was the highwater mark for the Internet “social movement.” It fused together, in a single unstable equilibrium, two otherwise irreconcilable experiences of 1969: on the one hand, the military-industrial complex’s dystopian preparations for nuclear apocalypse and on the other hand, the utopian spirit of a counterculture that yearned for self-fulfillment (and that once defined itself in opposition to the military industrial complex). Like wildflowers by the side of interstate highway, a set of neologisms sprouted up to beautify the otherwise bland architecture of this newly civilianized network. Cloud computing, social networking, podcasting, webcasting, crowdsourcing, wiki-ing, blogging, googling, tweeting, tagging, geotagging, liking, and above all, open access (“Information wants to be free”)—the new language of Web 2.0 gave voice to the energies of populations who imagined themselves freed by the network from the petty constraints of time and space. With Web 2.0, everything seemed to be possible: already implicitly the object of New Agey religious energies, the Internet was now even explicitly deified as a site for immortal life (provided, of course, that you take your vitamins).

To be sure, Web 2.0 was never all that its activists and prophets claimed for it. Repressed Palo Alto utopians liked to speak more about “transcending biology” than about the shamelessly biological work of their counterparts to the south in San Fernando Valley. But there was no denying it: Porn Valley and Silicon Valley went together like a horse and carriage. Already in 1998, David Foster Wallace reported that “adult software” was the most popular exhibit at the International Consumer Electronics Show; in 2002, the character “Trekkie Monster” from the Broadway Musical Avenue Q would definitively formulate the truth that Silicon Valley visionaries refused to admit to themselves: “The Internet is for Porn.” Facebook, for its part, tried to broker a compromise between the repressive sublimations of the Internet “social movement” and the repressive desublimations of the porn industry. It extended a specific model of predatory heteronormative sexuality–the “face book” that male freshman college students used to use in private to rank the attractiveness of college women–into the general paradigm for sociality itself. On Facebook as on other social media platforms, the spirit of New Agey self-fulfillment was soon lost in translation. “Following your bliss” quickly began to degrade into aggressive self-promotion and self-marketing; the Internet began to emerge as the natural habitat for neoliberalism’s “entrepreneurs of the self.” “Big Data,” meanwhile, allowed for the centralization of command and control of information databases by multinational corporations, just as our most insightful critics predicted in the years immediately following the introduction of the first personal computers in 1977. A technical milieu that was supposed to be defined by openness, sharing, and distribution began to be defined instead by paywalls and password protections, corporate tracking of individual consumers, massive data mining and sale of aggregate user data, the industrialization of external human memory, and the creation of profit through the strategic manipulation of data clouds. A space that was supposed to bring peoples, cultures, and ideas into contact with one another turned out to achieve the opposite: it functioned less as a crossroads or fora, than a hall of mirrors or echo chamber, a space that allowed for the self-righteous reinforcement of existing opinions, no matter how paranoid or ill-founded. Social networking, it turned out, was good for anti-social networking as well.

No doubt even more disenchantment awaits us just around the corner. Soon it will occur even to the most undialectical cyber-activist that “Open Access” is less a watchword for a challenge to intellectual property rights and for a coming democracy, than the polite term used by the neoliberal “price mechanism” when it wants to declare the labor of producing works of music, literature, poetry, and cinema to be completely worthless. No price, no value, no future: it is becoming increasingly clear that “Open Access” is one of the most effective disincentives modern society has ever created to discourage young people who wish to try to make a living creating poetry or literature, cinema or music (as distinct from merely consuming it, which is the economic instance on which Open Access cyber-activists tended to fixate). On the terms of Web 2.0, after all, creative works are nothing more than an unusually time-consuming subgenre of universally uncompensated “user-generated content.”

Still, even with all of these mounting “costs” becoming increasingly clear, it was still at least plausible to draw up a balance sheet on Web 2.0 that listed even greater “benefits,” and with increasing numbers of people bent over in public, thumbing their devices and laughing at private jokes, Web 2.0 was beginning to seem less like nuclear energy than Daylight Savings Time: a military innovation that didn’t remain alien to civil society, but that managed to translate itself seamlessly into the very fabric of ordinary everyday life.

To be continued . . .