6 Questions for Mark Schafer

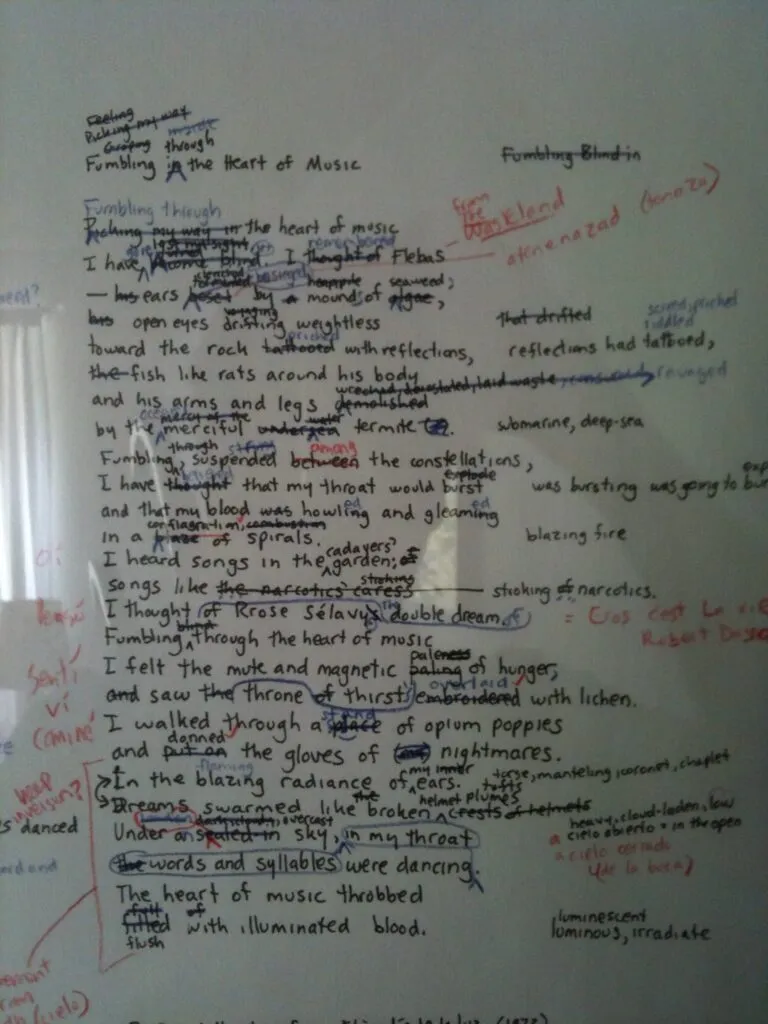

A light split the room where Rubén Darío was trying to write. On that side, a copy of Don Quixote; on this side, the untrimmed sheets of paper with words crossed out and the unread letter from a young poet in search of guidance and assistance.

—from Mark Schafer’s translation of David Huerta’s “Light Split in Madrid” (Volume 66, issue 3)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

The first pieces I ever translated were “The Fall” and “Swimming,” microstories by the bravura (and unnerving) Cuban author Virgilio Piñera (1912–1979). I read them in Spanish in a Latin American Literature class in college in the early 198s and was astonished by them. I wanted to share them with friends and family but none of his fiction had been translated into English. So, I came up with a brilliant idea: I proposed to the professor that instead of writing the upcoming paper she’d assigned, I would translate one of Piñera’s stories into English. She denied my request. But I’d caught the bug and, 42 years and two books of Piñera translations later, I’m still translating his masterful and supremely disturbing stories. More on that later.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

On the one hand, every writer and every work I’ve ever read influences the way I translate poems, stories, and novels from Spanish, since they all enrich and feed into the ineffably complex and continually expanding experience I have of language. I am convinced that any person’s experience of language is more complex and multifaceted than a “neural machine” could ever be. (See my recent essay about this, “Translation is Original, Creative Writing,” in Delos: A Journal of Translation and World Literature.)

On the other hand, I’d say that each writer, each work I translate influences how I write that particular translation. Yes, translation is “hard” (i.e. complicated and requiring a lot of effort to get it to work.) But it’s also “easy.” The source text, an expression of the author’s experience and mind, is always there to talk to you, to show you what the author did and meant (even if it’s not clear), to encourage and to demand that you do just as much and just as well with your mind and your language. I’ve had the luxury and choice over my career to date to translate almost exclusively texts that I find absolutely fascinating, in one way or another. What greater pleasure and satisfaction than to take on such challenges—and with the unflagging and unyielding support of the texts and the authors themselves!

What inspired you to translate this piece?

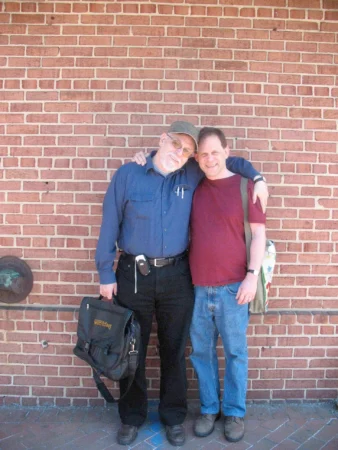

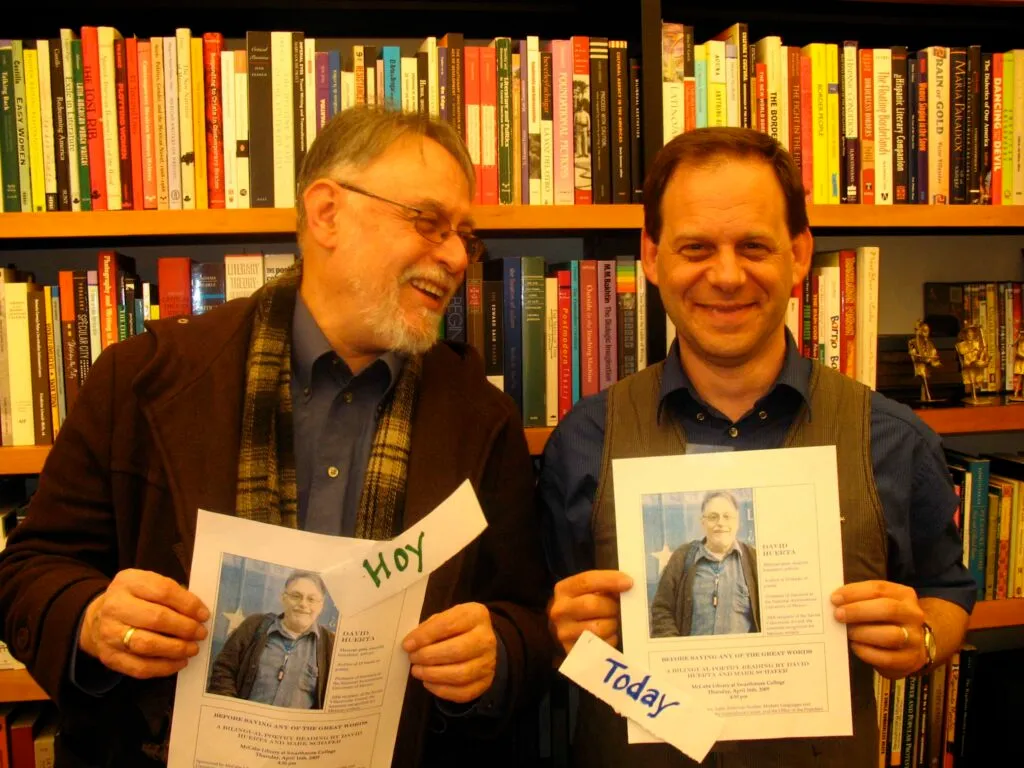

In the mid to late-1990s, the Mexican poet David Huerta reached out to me through a mutual friend to see if I’d be interested in translating a dozen new poems of his into English for an upcoming reading he was scheduled to give in California. I read them and fell in love with his poetry: his linguistic precision, his love of life in all of its rich and fascinating messiness, his commitment to language in all of its complexity and specificity, his passionate humanity. (See my “Elogio y agradecimiento a David Huerta” for more (in Spanish) of what I loved and appreciated about David.) Those translations were the beginning of an ever-deepening professional and personal relationship with David that culminated in my translated, career-spanning anthology of his poetry, Before Saying Any of the Great Words: Selected Poems (Copper Canyon Press) and my love for him as a brother.

In 2019, on the plane to the Guadalajara Book Fair, where David would receive the prestigious FIL Literature Award in Romance Languages, I read what turned out to be one of his last books of poetry, the collection of prose poems El ovillo y la brisa. That book was so delightful it made me laugh out loud in the plane. I promised him then that I’d translate it into English. Six years later, and three years after his untimely and devastating death, I am halfway through translating the book. “Light Split in Madrid,” published in this issue of The Massachusetts Review, is from this collection. I’m especially looking forward (with some dread) to translating the poems from that book that I think are literally impossible to translate. I guess I’ll have to translate them non-literally….

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

The town of Tepoztlán in central México, where I lived for three and a half years in the late 1980s and early 1990s and where I became not only a fluent Spanish speaker but gained fluency as a member of the Spanish-speaking world, influences everything I’ve translated since then. I remember going to the plaza, the marketplace, and realizing that a plátano was not a banana because a banana was something found in supermarkets whereas plátanos are native to mercados (among other places). I remember when I started to notice that I didn’t know whether, in the dreams I remembered from the night before, people had been speaking English or Spanish. I remember the shift from feeling of laboriously assembling two or three clauses into a multipart sentence to the thrill of feeling that I could ride a high-speed roller coaster of clauses for as long as I chose. Tepoztlán (the people, the place, the history, the life, the ritual time, and more) was where I came to know Spanish as a way of living, a way of relating to the world, where I acquired membership in a Spanish-speaking community, rather than “a language.” It’s where Spanish came to life in me and I in it. And it’s still my one of my two homes.

What are you working on currently?

As I mentioned earlier, I’m in the long process of translating into English David Huerta’s collection of prose poems, El ovillo y la brisa (THE SKEIN AND THE BREEZE)—from which “Light Split in Madrid” comes—in its entirety. Many of my translation projects seem to take me ten years or more. This one may actually clock in at a mere five years. But first, I have to finish my (re)translation of 68 stories by the Cuban author Virgilio Piñera. In 1987, just as I was finishing my very first translation, Cold Tales, a collection of 44 stories by Piñera, not one but two collections of Piñera’s previously unpublished short stories were published in Spanish in Cuba. Over the ensuing 37 years, I kept meaning to get back and “finish” the job I’d started (unknowingly) in college in the early 1980s. But other things (nine other books, among other things) kept getting in the way. It took a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Translation Fellowship, which I received last year (on my third attempt) to turn that back burner back into a front burner. I feel honored that New York Review Books has committed to publishing this vastly expanded (by newly translated 24 stories) and revised (the previous 44) collection of short fiction by Virgilio Piñera, along with my revised translation of his major novel, René’s Flesh. Now I just have to finish translating the stories…

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I do work in other art forms! I’m a literary artist, a visual artist, and a conceptual artist. Another way of putting it is that I love to play with words, images, and concepts, separately and in various combinations. These have ranged from an extensive series of subjective map collages, which I called “shortcut maps,” to Born To Be Happy, a children’s book I wrote for my daughter; from “Winterlights: A Circle of Peace,” a light-based public art installation in Roxbury’s Highland Park neighborhood created with Yvon Augustin and local teenagers, to my work coordinating the design and creation of “An Ode to Africa in the America,” the 9’ x 85’ community mural installed two years ago on the campus of Roxbury Community College. Most recently, I conceived of and created an audio piece entitled “One Hundred Blasts, Two Women, A Single Cry of Grief: An audio meditation on Israel/Palestine/Gaza for the High Holy Days” for my Jewish congregation, Dorshei Tzedek in West Newton, MA.

MARK SCHAFER is a translator, visual artist and arts activist, and a senior lecturer in Spanish at the University of Massachusetts Boston. His translations include Migrations: Poem, 1976–2020, Gloria Gervitz’s monumental life work, Belén Gopegui’s novel Stay This Day and Night with Me, and Before Saying Any of the Great Words: Selected Poems, an anthology of the poetry of David Huerta. He lives in Roxbury, MA, the traditional and unceded territory of the Massachusett and Wampanoag Peoples.