Statues Fell. Racism Never Left.

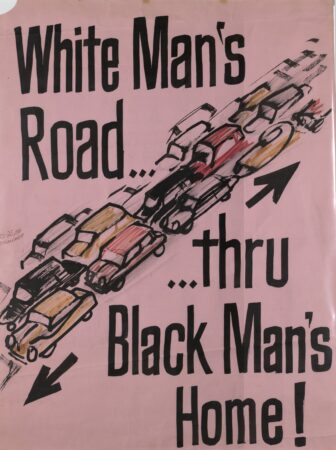

Photo from Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis, DC Public Library, 1969.

In October, U.S. National Park Service employees reinstalled a statue of Confederate military officer Albert Pike at the corner of Third and D Streets NW in Washington, DC’s Judiciary Square. Pike died in 1891 and Congress approved the statue’s initial construction shortly after, over the objections of Union army veterans. By the time protestors ripped the statue off its pedestal in June 2020, it had already generated several rallies demanding the removal of a known white supremacist from such a place of prominence.

The National Park Service restored Pike’s statue in response to an executive order from the current president. A section of that order titled “Restoring Truth in American History” mandates the reinstallation of any federal monuments removed since January 2020. This meant replacing Pike’s statue and a Confederate memorial in Arlington National Cemetery as quickly as possible, at an estimated cost of more than $10 million.

The pedestal of Pike’s statue describes him as “Author – Poet – Scholar – Soldier – Philanthropist – Philosopher.” It also credits his participation in a local Masonic organization. The dedication omits how Pike’s regiment scalped Union troops. It leaves unsaid the truth that he never renounced racist commitments to white supremacy.

Pike advanced those commitments until his death. Years after the end of the Civil War, he declared, “We mean that the white race, and that race alone, shall govern this country. It is the only one that is fit to govern, and it is the only one that shall.”

There is something fitting about reinstalling a statue of Albert Pike under the guise of “Restoring Truth” to understandings of American life. Venerating white supremacists while conveniently sidestepping their racism is routine in the United States. Most recently, it includes pushing people out of jobs for pointing out when public figures have longstanding records of explicit racism.

Putting Pike back on a pedestal also materializes how tearing down statues might have temporarily made room to celebrate other people in the public square, but it did not end racism. Racism endured even as monuments to racists came down.

Before being downed by protestors in 2020, the statue of Albert Pike was previously removed from its original location and rebuilt nearby to make room for expressway construction. The 1956 plan for a federal highway system envisioned a network of highways speeding commuters into DC’s central business district from what were at the time rapidly expanding, overwhelmingly white Maryland and Virginia suburbs.

DC residents formed multiracial coalitions to oppose a highway network atop their city. Efforts to build parts of the network across majority-white neighborhoods ground to a halt. But other sections went forward. The construction flattened most of Southwest DC, permanently displacing 23,500 residents, nearly two-thirds of them Black people. After the dust settled, Albert Pike’s statue got a new home.

The paths that expressways carved through DC resemble scars left in central cities across the country. Building out America’s highways is estimated to have displaced more than 475,000 households, totaling more than one million people. From Charlotte to Seattle, from Milwaukee to Miami, and from Hartford to Los Angeles, when new roads needed to run over existing neighborhoods, the neighborhoods chosen were usually those of racially and ethnically marginalized communities. Nationwide, most of the people who lost their homes to build the American interstate system were Black.

Sometimes, highway construction was explicitly racist by design. Detroit’s midcentury political actors, for example, shaped the construction of what is now the Chrysler Freeway to cut through the heart of dense, majority-Black neighborhoods and skirt around industrial facilities owned by white economic elites. Despite numbering only 16% of the population at the time, 75% of the residents evicted to build the city’s highways were Black. Many displaced people were never fully compensated for the value of lost homes and businesses. Some received no compensation at all.

In other cases, the burdens of expressways landed in racially unequal ways, even if there isn’t definitive evidence of racists at the wheel. DC’s freeways are prime examples. Echoing a refrain heard across the country, the people who plotted routes through the District insisted their decisions were not made based on race, but tied to locations where property values were lowest. And yet, because property valuation is predicated on racist logics, the result was bulldozers rolling forward across majority-Black neighborhoods and stopping short of majority-white ones. Such occurrences demonstrate how racism is a matter of consequences that can accrue with and without explicit intent.

And the racist consequences of America’s highway infrastructure are far-reaching. Federally subsidized expressways facilitated the creation of all-white suburban municipalities. They subsequently maintained those municipalities as privileged hubs of economic opportunities for decades after civil rights statutes outlawed explicit racial discrimination.

Highways rammed through existing neighborhoods also created concentrated sources of harmful pollutants. Public health research links racial disparities in the distribution of tailpipe emissions to racial disparities in asthma and respiratory health conditions. Because neighborhoods torn apart by construction tended to be economically and racially disenfranchised, especially but not only low-income Black communities, areas that contend with the brunt of highway emissions today tend to be economically and racially disenfranchised, especially but not only low-income Black communities.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation initiated programs to address the racially unequal consequences of the nation’s federally subsidized highway network. Funds were available for citizen-led efforts to equalize access to safe, healthy communities. Projects included covering highways with greenspace to reduce local pollution burdens, installing pedestrian connections across highways to facilitate access between neighborhoods, and creating rapid transit links to connect people to employment. The current administration canceled these programs, including already funded projects.

Together, Albert Pike’s statue and the highway system it exists alongside show us some truths about the United States. They show us how racism is in our face across this country. Orders to restore Pike’s statue show us how people with the power to do otherwise are affirmatively choosing to honor white supremacists. Celebrating white supremacists who make their commitments publicly known is always a choice.

But racism was in our faces across this country even when statues of racists like Albert Pike were out of sight. Racism extends far beyond the words and actions of individual racists. Like highways, it is embedded in the everyday construction of our American landscape. Remedying it will take so much more than tearing down statues.

NICHOLAS CAVERLY is author of Demolishing Detroit: How Structural Racism Endures (Stanford University Press, 2025) and was a 2025 fellow in the University of Massachusetts Interdisciplinary Studies Institute.