10 Questions for Jack Saebyok Jung

I greet an ancient refrigerator,

once my father, now reduced to bare bones, yet

it remains unbearably heavy.

—from Jack Saebyok Jung’s translation of Heeum’s “The Use of a Window” (Volume 66, issue 3)

Tell us about one of the first pieces you translated.

One of the earliest pieces I translated was a poem by Yi Sang during college. I was drawn to the strangeness of his imagery and the way his fractured syntax mirrored the ruptures of Korean history, as well as the fractures of the world then and now, and even the fragmentation of our desperate modern lives. I had almost no training at the time, but I felt an urgency to carry those sounds into English, even if imperfectly. Looking back, I think I was trying to piece together parts of myself into a language of my own between Korean and English. That first attempt taught me that translation is as much about listening and inhabiting as it is about rendering.

What writer(s) or works have influenced the way you write now?

As a poet, I’ve been shaped by both Korean modernists like Yi Sang, as well as contemporary masters like Kim Hyesoon. I am also deeply indebted to American poets such as Harryette Mullen and C. D. Wright. My teachers and mentors, Don Mee Choi, Lucie Brock-Broido, Jorie Graham, and Mark Levine have been great influences on my work as well. Their work showed me how form can hold both personal and collective histories. As a translator, Heeum’s spare, resonant lines have influenced how I think about silence, gaps, and atmosphere in my own writing.

What other professions have you worked in?

Most of my professional life has been rooted in literature, teaching creative writing and translation. Early on, I interned at Boston Review under Timothy Donnelly, which gave me insight into the editorial side of publishing. I’ve also taught across a range of contexts, from the University of Iowa to my current position at Davidson College. In a sense, my “other professions” have all orbited around poetry, whether through teaching, editing, or translating, though each role has given me a different vantage point on how literature enters the world.

What did you want to be when you were young?

When I was young, I wanted to be an artist of some kind. Sometimes a cartoonist, sometimes a novelist. Translation came later, but it felt like a natural extension of those early impulses: to make something that connects imagination with the world.

What inspired you to translate this piece?

Heeum’s poems captivated me because of their “rare sound,” which is a literal translation of her pen name, both elusive and resonant. I was moved by how she could take an everyday object, like a refrigerator or a chair, and reveal it as a site of mourning, memory, or mystery. Translating her felt like learning to attune myself to a frequency just beyond ordinary hearing.

Is there a city or place, real or imagined, that influences your writing?

Butler, Missouri; Edmonton, Alberta; New Haven, Connecticut; Iowa City, Iowa; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Davidson, North Carolina. It may be different now, but I’ve often found myself in places in North America with very little Korean presence compared to the larger hubs. I think that shaped the way I came to see translation—as a means of defining my place in a world where I often felt alone. And Seoul, South Korea, where I return often, is both real and imagined for me: a city layered with personal history, ancestral memory, and the ongoing vitality of contemporary Korean literature. Much of my writing and translation lives in the tension and resonance between these places: rural and urban, North American and Korean, remembered and imagined.

Do you have any rituals or traditions that you do in order to translate?

My main ritual is reading the poem aloud—first in Korean, then in English—many times over. It allows me to feel where the breath catches. I also tend to work best at night, when the world is quieter.

If you could work in another art form what would it be?

I would choose film, particularly editing. The way film cuts and juxtaposes images feels close to how I think of poetry and translation, where meaning emerges in the transitions, in what is left unsaid as much as in what is shown. I also think a lot about video games, which share something with both film and poetry: they create meaning through fragments, atmosphere, and player choice. Games have taught me to see narrative as nonlinear and participatory, which echoes the way I approach poems and translations, less as fixed objects than as experiences unfolding.

What are you working on currently?

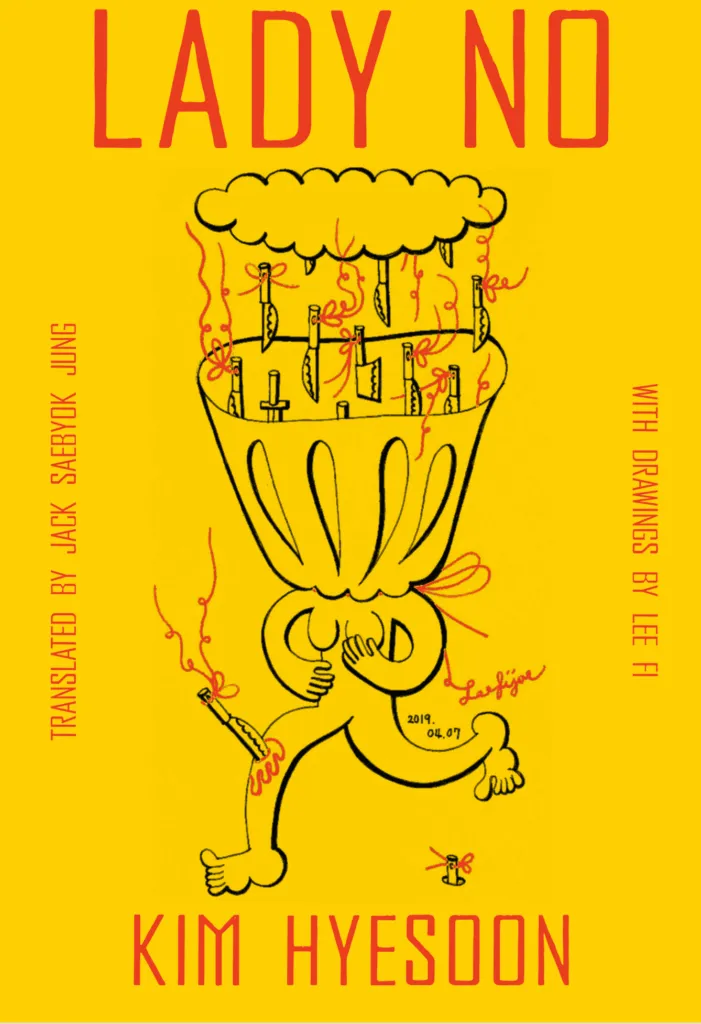

I’m working on a full-length translation of Heeum’s poetry collection Skirts Face Each Other Without Lifting Skirts, as well as finishing up my translation of Kim Hyesoon’s forthcoming book Lady No, which will be published by Ecco. Alongside these, I’m revising translations of Kim Sowol’s poetry and Kim Bokhui’s Sweet Porosity, and preparing the Korean edition of Franny Choi’s Soft Science. I have also just finished drafts of full translations two Korean poets from 1920s: Kim Sowol and Han Yong-un.

Of my own work, I’ve just published my debut collection Hocus Pocus Bogus Locus, and I’m at work on two new manuscripts: Floating Worlds, which experiments with cosmic, diasporic, and digital themes, a revisionary project drawing on over a decade of poems. I’m also writing a cycle that fuses video game mechanics with lyric forms, which involves a long sequence on the Korean afterlife judges, the Ten Kings.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home, alongside recent Korean poetry collections and classic Korean novels. These include Park Wan-suh’s Namok (The Naked Tree in English), about a young woman’s coming of age during the Korean War, and Kim Hoon’s Hyun-ui Norae (The Song of the Strings), which follows a medieval musician’s existential struggles as he loses his country, becomes a refugee, and invents the Korean zither, the gayageum.

JACK SAEBYOK JUNG is a 2024 NEA Translation Fellow and the author of Hocus Pocus Bogus Locus (Black Square Editions). A Truman Capote Fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he co-translated Yi Sang: Selected Works (Wave Books), winner of the MLA’s Scaglione Prize. He teaches at Davidson College.