Memorial Wall

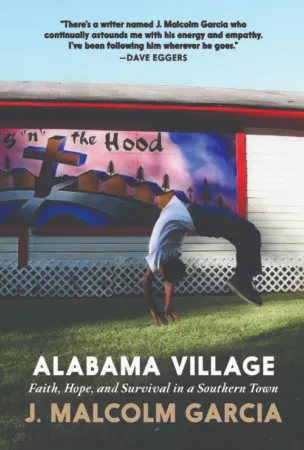

A Review of J. Malcolm Garcia’s Alabama Village: Faith, Hope, and Survival in a Southern Town (Seven Stories, 2025)

From the get-go, let it be clear: this will be a partisan review. Early on, during the four-year-plus project that became Alabama Village, Malcolm mentioned to me in an email what he was working on and even sent me a snippet or two. I told him I suspected this would be a magnum opus—a book that would bring to bear, and bring together, everything he’d done up to this point, from his years as a social worker in San Francisco to his time reporting from the war zones of Afghanistan and Syria. Now that I have that work in hand, I’m happy to say I was wrong. The book is far better than I could ever have imagined. It’s a ragged-edged, crystalline masterpiece: a document of our times, a meditation on the society we’ve created, and a work of testimony that will speak to readers for many years to come.

Alabama Village, a war housing project built during WWII as family homes for Mobile’s shipbuilding industry, is a long way from Afghanistan. A lot closer to home. Yet according to a recent PBS documentary, this small community, part of Prichard, Alabama, just five miles south of Mobile, is “a place most locals have never heard of, or won’t go near, the most violent, impoverished community in the state.” When it first aired, the PBS show also compared life in the Village to the civil war then raging in Syria (1). Garcia’s intro gives a summary of factors that led to this present: white flight, followed by absentee landlords and abandoned properties, then closed businesses and declining tax revenues—along with political corruption, failing infrastructure, and a near total absence of basic city services. In 2013, the neighboring city of Chickasaw erected barricades to block a street that connects it with Alabama Village.

Despite his fourteen years serving the unhoused in San Francisco during the crack epidemic, Garcia declares, “what I saw in the Village was on a scale beyond anything I’d ever experienced.” When he became a journalist, Garcia notes, he “devoted [him]self to covering families like [his] former homeless clients,” people who, “in the unlikely or unfortunate event they become noteworthy, are generally viewed with disdain” (3-4). To find out more, Malcolm called up John Eads, co-founder, with his wife Delores Eads, of Alabama Village’s Light of the Village church. The pastor welcomes his interest, and when a magazine editor shows enthusiasm as well, Malcolm heads to Alabama.

Focusing any further on the author, however, would do a disservice to his work. After his half-dozen pages of intro, Malcolm disappears entirely. In fact, the book doesn’t even begin with that intro, which it calls an “Overture”; it starts instead with a “Prelude”—a short portrait of Tony “TJ” Brisker, the young man and churchgoer whose photo would become the first posted by John and Delores on the Light of the Village’s Memorial Wall. From that dark day in 2009 to the time when Garcia’s book went to press, “dozens of more photos of mostly young black men,” were taped up beside it. Their names and the dates of their deaths are listed on the final pages of Alabama Village.

Garcia notes,

As a social worker, I worked with religious people and found they did not stick around long when their prayers went unanswered. Too often they suggested the homeless men and women I worked with didn’t have faith. John and Delores, however, had stuck with it for twenty years. Surely, they’ve suffered disappointment. Surely, some of their prayers have gone unanswered. But they stayed. They had to be more than do-good Jesus people. (4)

We hear TJ’s story as remembered and experienced by the Eads. In general, we’re told, they “felt each passing. […] They spoke at their funerals and mourned their absence. Because of how they lived, their deaths, although tragic, did not surprise them. TJ’s death, however, did” (ix).

In the pages of Alabama Village, we also learn about other young black men through the memories and stories of John and Delores. But focusing only there would also be a disservice: This is not a book about a Black community written by a passably white writer told from the perspective of mostly white evangelicals. This is a story of structural racism, politically imposed poverty, and criminal societal neglect told by the community members themselves.

Ten of the fourteen chapters in Part One begin with a first name in the first sentence; each is essentially a character sketch, and only one name (Da’Cino) is repeated. The choral structure of Part Two—titled “Portraits”— is even more explicit; its sixteen chapters again focus largely on single characters, with a second figure often introduced at the close, to be featured in the chapter that follows. Each of the names from Part One returns and others are introduced, including elders who recount Village history and reflect on its present. These dramatis personae never equal the count of photos on the Memorial Wall, but through accretion we are given a rich, complex weave of stories, and we feel their weight.

The most obvious sections to sample come from Bigg Man, whose life serves to frame, punctuate, and bookend Alabama Village, or that of Da’Cino, with his two chapters in Part One and another in Part Two. On the former: “Corey Davis was his given name but everyone—except Miz Phyllis—called him Bigg Man, even when he was small. He was a fat little boy with a cocky confidence that lent itself to the nickname” (10). Miz Phyllis raised Corey, together with her own son Lawrence, so she knows: “Bigg Man is a twenty-four-hour hustler. He can lose it all in a dice game and two weeks later get it back. A hustler hustles. He’s not a gangster. A gangster takes what they want. They watch other people hustle and try to take it from them” (13).

On the latter:

Da’Cino grew up in the Village and was about eight years old when he first saw John and Dolores playing games with other children near the abandoned crack house. He was cutting grass with his stepdad, Joe. Da’Cino always worked. At first with Joe and then on his own when he grew older. (17)

Later, we get to know that stepdad better. We also hear about Da’Cino’s promotion to managing a multiplex cinema, a job he loses due to COVID. Afterwards, no employer responds to his resumé, so he returns to work for the church.

Rather than more about these central figures, however, I’ll cite here lines that sketch out Aaron Amison, a young man who, as a child, “fed his grandmama’s goats, and from that day everyone called him Billy Boy” (103). “[Billy Boy] does a lot of walking, rapping to himself without paper or pencil. Freestyling. Gives him peace of mind” (107).

He will turn twenty-eight in a few days. A lot of years, man, a lot of years, for real. Maybe not for the pretty people in Mobile and the suburbs, but for him and his homeboys, yeah, a lot of years. The pretty people have no knowledge and mostly no interest in a brother like him. He doubts any of them would be surprised to see their twenty-eighth birthday. (107)

We could take a close look at the dialogic art throughout this monologue and elsewhere in the book, at its code switching, freestyling, and free indirect discourse, but it’s time to cut to the chase. As Alabama Village is spinning toward its conclusion, Billy Boy reappears, in a moment where his peregrinations have brought him back to the church, and back to its Memorial Wall. He touches the photos of two of his closest friends, “stares at them a moment longer, then turns and walks outside” (235). He then spots Da’Cino and “asks him to hit John up for some shoes” (235).

John needs to pick up kids for their after-school program, so Billy Boy asks to ride along in the van. As they ride, the two talk a bit, then, after John gets the kids back and inside, he waves Da’Cino over: “I got a hundred bucks. That should handle the shoes. I’ll tell him and then you want to run him up real quick to the store?” (238). The lines that follow say everything:

Da’Cino gives him a look. He thinks John can be too nice sometimes, but he knows John sees potential in everybody. […] John knows he disapproves but what should he do? Write Billy Boy off? Say, I don’t want you around here anymore? How would that help? Enabling, the textbooks call it. It’s easy to sit at home and recite academic rules of social work about what should and should not be done. In the field, it’s much harder to do. John deals with people, not words on a page. […] It’s just shoes. A fleeting moment of happiness. Why not? Enabling. That’s a good term. John supposes it applies to him.

Go get you a birthday gift, he tells Billy Boy and hands him the money. Da’Cino will take you. Then we’ll deal with finding you a place to stay.

Billy Boy looks at the ground. He rubs the back of his right hand against his forehead. The evening closes around him. He takes the money without looking up.

Y’all going to make me cry, he says softly. (239)

There’s nothing abstract, and nothing academic, about J. Malcolm Garcia’s Alabama Village. The stories it collects are as concrete and vivid as those Memorial Wall photos, and, like any memorial, its lessons are for the living. More than any other—and more than enough—is Garcia’s simple commitment to seeing, hearing, and recording the people and history of a place that nearly everyone else has written off. The space of a memorial is, in some sense, sacred. Not because it saves anyone—but because it rejects things as they are and lays down the world as it is. To build one, though, you do have to stick around. And see the potential in everyone.